Honduras’ Overlapping Crises Have Their Roots in Land and Natural Resource Policy Failures

By Christen Corcoran and Malcolm Childress

The convergence of the pandemic, climate shocks, and militarized borders presents a dire situation for human rights. Will the Biden administration prioritize support for vulnerable populations in securing land and resource rights and livelihoods to build social safety nets for crisis resiliency?

Over the course of several days between Jan 14th and Jan 18th 2021, at least 8,000 asylum seekers attempted to cross the border between Honduras and Guatemala. Many people were shocked, but perhaps not surprised, to see the images of heavily militarized, armored troops beating back the waves of Honduran asylum-seekers with the all-too-familiar arsenal of batons, rubber bullets and tear gas. This is only the latest brutality faced by the asylum seekers, who have been forced to endure criminal violence, long-standing food and livelihood insecurity, economic insecurity from the COVID19 pandemic, and the devastation of two hurricanes that hit the country in late 2020.

Explanations of migration from Honduras tend to focus on immediate causes. “Push” factors including persecution and extortion from violent gangs, lack of economic opportunities, and disillusionment to the system are often spotlighted. But to better understand the root causes of these push factors, and of the images we are seeing, — why so many would leave their generational homes, abandon most possessions, and embark by foot on a 2,000+ km journey— we need to take a closer look at the ownership of land and natural resources in Honduras.

A legacy of unequal land ownership

Honduras’ largely rural and impoverished population depends on rainfed agriculture as its main source of livelihood. The majority of the asylum seekers come from the country’s southern and western regions, where food insecurity is acute. Their agricultural-based livelihoods are extremely vulnerable due to Honduras’ highly unequal distribution of land, ecological deterioration, and the natural disasters associated especially with climate-induced shocks.

As the original so-called ‘banana republic’, Honduras has never provided sufficient land and natural resource endowments for its citizens to create sustainable and dignified livelihoods on a widespread basis. The country’s rural impoverishment has also prevented a truly democratic form of governance from taking root, leading to the current situation of widespread corruption and violence.

Honduras is largely mountainous, and prime agricultural land is only found in the northern coastal plain and a limited number of valleys and plateaus. For much of the 20th century, these lands were controlled by foreign fruit companies and local elites who tended to focus on cattle ranching. The bulk of the rural population lived around the edges of these operations or in the mountains, often denuding forest to create small hillside forests for subsistence crops. In the 1970’s and 1980’s, agrarian reform policies were instituted with the aim of changing the highly unequal distribution of land to give workers ownership in the banana, African palm and sugar sectors, and bring previously landless workers on the productive coastal and valley land. But apart from a few early successes, these agrarian reforms were resisted by elites and only weakly implemented. By the end of the 1980s this situation had led to stagnation in agriculture, widespread insecurity around land rights and continuing rural poverty. ‘

In the wake of the end of the Cold War, in the early 1990s government instituted market-oriented rural policies which protected most existing land rights through a focus on land titling and registration upgrading (although very little indigenous land was titled during this period) and reduced government involvement in agricultural markets. This wave of market-oriented reforms led to expansion of some commodities like African palm oil, but failed to lift the majority of rural residents out of poverty. While labor-intensive maquiladora (assembly of clothing and shoes) and urban service sectors, along with increased migration to the U.S., covered up the structural failures of the economy during the 1990s and 2000s, rural vulnerability continued to intensify. Many migrated to informal settlements in urban areas like San Pedro Sula where underemployment and state-failure provided fertile ground for the rise of gangs and drug trafficking organizations. San Pedro Sula had the highest homicide rate of any city in the world for several years in the 2010s.

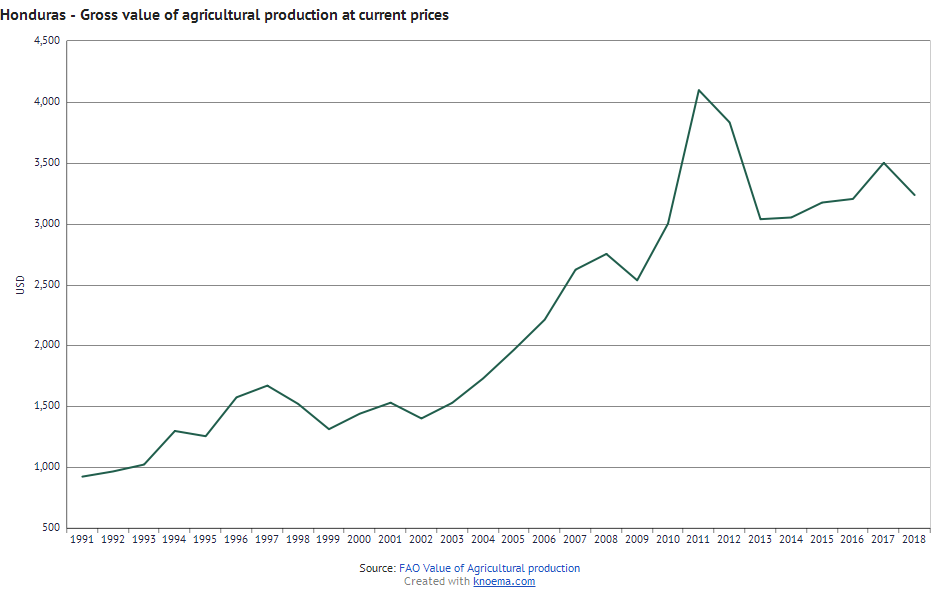

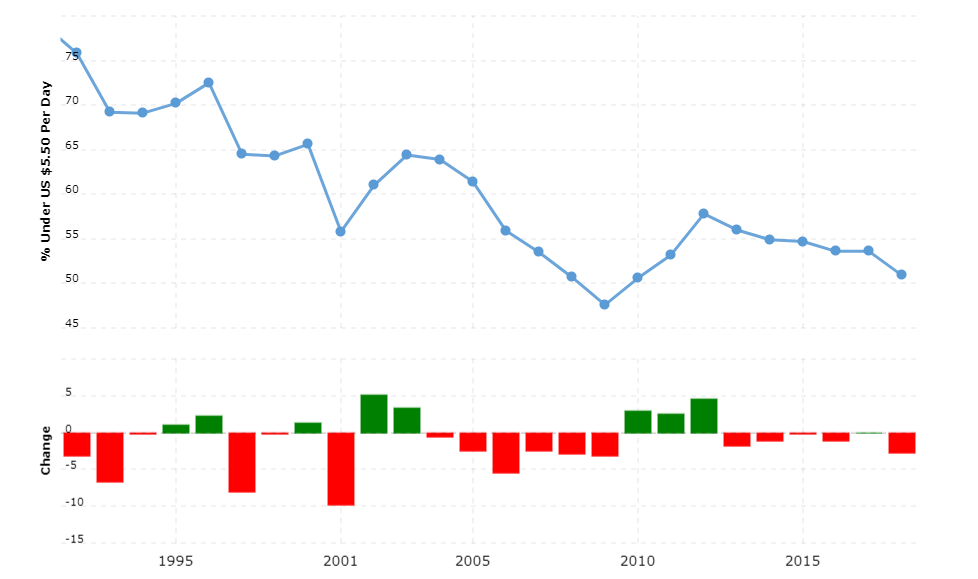

As indicated in the charts of agricultural growth and poverty rates, agricultural growth and poverty reduction are decoupled. Most of the increase in agricultural growth has come from land extensive expansion in African palm, cattle or bananas, with some growth in coffee and newer exports like pineapple and melons.. Poverty remains above 50% nationally, and 60% in rural areas, despite an upward trend in agricultural growth. Resource and land access, and smallholder productivity, have never been adequately addressed to support impoverished Honduras, especially for Indigenous and rural communities.

Weak governance, ecological deterioration and climate shocks

Since the coup-like ouster of the Zelaya government in 2009, governance in Honduras has worsened, with allegations of corruption and narco-trafficking relationships in high places. Since 2009, mining, hydroelectric power projects, and mass tourism have also expanded, putting further pressure on the land resource and rural population’s livelihoods.

Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous communities have suffered the bulk of dispossession as many of the untapped natural resources are found in their territories. Even some climate mitigation initiatives have paradoxically led to the dispossession of communities and repression of grassroots leaders. Indigenous and environmental activist Berta Caceres was murdered in 2016 for defending the territorial rights of the Lenca people against a hydroelectric dam on the Gualcarque River.

The government has failed to create reliable social safety nets, starting with strong territorial and land rights. It continues to support encroachment of mining and other industries over the territories of Indigenous peoples, small-scale farmers, and Afro-Indigenous Garifunas.

The combination of vulnerability and climate-induced shocks are making land-based livelihoods impossible for many Hondurans. The ongoing ecological deterioration from hillside agriculture, extractive industries and poor management of river basins has made Honduras even more vulnerable to the shock of repeated hurricanes -- particularly through hurricane-related flooding. In between hurricanes, droughts have caused an increase in crop pests and disease, such as coffee rust, as well as a failure of rainfed crops, pushing people to abandon their land. Impoverished refugees fleeing climatic and man-made catastrophes in Honduras are a regional feature with departures steadily rising since 2010 and reaching 247,000 in 2019.

The COVID-19 pandemic has added more dimensions of vulnerability, contracting the GDP by an estimated 7.1% in 2020, making the situation even worse for Honduras’ poor, near poor and middle class.

In late 2020, when back-to-back hurricanes Eta and Iota lashed Central America with sustained winds and rain, the landscape suffered deadly landslides, mudslides, flash flooding and destruction. It is estimated that these hurricanes alone destroyed 40 percent of the nation’s GDP. For smallholder farmers, especially those in Western departments Copán, Ocotepeque and Lempira, the loss of harvest and home intensified COVID-19 hardships of lack of healthcare, market disruptions and food scarcity. As one farmer explained:

“On Wednesday evening, strong water streams coming from the flooded river of Higuito destroyed parts of my house and farm. Our harvest was ready in two weeks, we’re barely left with a roof over our heads” -Francisco Monroy, a smallholder coffee farmer from Ocotepeque, Honduras

An estimated 150,000 were displaced and left unhoused from the damage of these hurricanes. Families managed to sleep where they could. Severe health conditions led to outbreaks including skin rashes, stomach problems, dengue, and the further spread of COVID19. There was an almost complete absence of government support for rural-dwellers, who were left to fend for themselves.

“We don't want to live in Honduras anymore, there isn't any work. There are no opportunities, We are leaving because we don't want to suffer further." one individual told Agence France-Presse

There are few options left to citizens when land and other assets are devastated, livelihoods are lost, and physical security is threatened. It is no surprise that USAID, among others, predicted that these circumstances would only lead to further waves of mass migration.

Closed borders close off the social safety valve and facilitate human rights violations

In the past refugees from Central America’s wars and disasters could make their way north to seek asylum. Recent border closings and restrictions of mobility in the region have made refuge for asylum seekers an even more difficult and dangerous undertaking. When the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the highly infectious COVID-19 a public-health emergency, the agency explicitly advised nations to keep borders open; however, governments in the region have responded overwhelmingly in the opposite direction. COVID-19 has offered another justification to restrict mobility, and it has been utilized across the region by U.S., Honduran, Guatemalan, and Mexican governments.

The social safety valves of human migration are being cut off by the Honduran government, which issued a mandate to stop caravans and mobility. Some departing caravans were stopped before leaving the country and turned back to a home that no longer exists. As UNHCR spokesperson Andrej Mahecic explained: “Restrictions on movement make it harder for those that need help and protection to obtain it, and those that need to flee to save their lives are facing increased hurdles to find safety”. The border between Guatemala and Mexico is also now militarized to prevent movement. Both globally and in the region the pandemic has been used as a justification for further constriction of international borders.

Hardened borders are turning long-simmering crises of livelihoods and insecurity into humanitarian crises which can easily violate international human rights law. During a crisis, or multiple crises, executive powers have a tendency to place significance and intense focus on borders. Emergencies allow the executive bodies to consolidate power to respond quickly to crisis, placing these actions outside of the international legal codes. In these extra-legal circumstances, human rights violations towards those seeking refuge can proliferate without oversight, and can include “a denial of civil and political rights such as arbitrary detention, torture, or a lack of due process,”

The militarization of borders along Guatemala and Mexico, backed by U.S policies, is not only restricting the flow of legitimate asylum seekers, but detaining migrants and treating them as criminals. This makes the role of the state as guarantors of the rights and protection of the individuals murky at best, and perhaps comes to target the political and legal identity of the asylum seekers.

Will the Biden Administration shift policy?

The Biden Administration has pledged to respond with more “compassionate” immigration and border policies during his presidency. But the issues of why so many Hondurans are willing to risk their lives to leave their homes and families, and how to deal with it require a much wider perspective. Migration is linked to the overlapping crises of climate change, natural disasters and natural resource management, COVID19 pandemic, inequality and insecurity of land ownership, failures of governance, and failed regional policies with respect to migration, which must be addressed by the Biden Administration as well. As the main backer of the Honduran government, biggest trading partner and target destination for its asylum-seekers, the U.S. has a particular responsibility to respond. American journalist, Jeremy Scahill, put it this way:

“If you know this history, particularly in Honduras, then you know that what we are seeing now is a situation where the U.S. set a house on fire, and as the flames have raged, the U.S. is standing against the people trying to flee the fire that Washington set to their home.”

If humanitarian compassion, development, security and environmental sustainability are among its policy goals, the Biden administration and President Hernández must go further than simply tinkering with border policy. They need to support resiliency through addressing root causes of the crises in supporting national policies of agrarian and land reform which support small scale-farmers, collective land rights of Indigenous people, and safety nets for these communities to climatic shocks.

The case of the asylum seekers from Honduras is a sign of what is to come as climate change is estimated to create 1 billion climate refugees[1]. How we respond to these crises in Honduras could also serve as a roadmap for future responses. To do this, there must be an emphasis on building resiliency through social safety nets so that shocks do not destroy communities and livelihoods. As the leading contributor to emissions driving climate change, and the key international supporter of the Honduran government, the US has an obligation to help address the roots of the migration crisis. We must commit to supporting asset rights and livelihoods in Honduras, especially, and also around the world. When we see waves of refugees being beaten at border crossings we need to see past the emotive and fear-based reaction of short-term migration policies and look to land access and rights, and empowered local stewardship of natural resources as the solutions.

[1] The drivers of displacement in Honduras are not happening in a vacuum. Globally, we are witnessing exponential increase in climatic shocks and ecological breakdown that are beginning to set the scene for a potentially massive increase in climate migrants. Simultaneously, governments around the world are also blocking human flow through borders and unevenly allocating health services to its citizens in response to the COVID19 pandemic. These catastrophes are happening together, and layering on top of one another, and intermixing with “normal” dynamics of inequities which fuel economic displacement. We must act and learn from those displaced from Honduras to mitigate future suffering from each of these crises