Can We Bend the Curve on Land Governance by 2020?

(BY MALCOLM CHILDRESS)

The period 2015-2020 may become one of the most dynamic periods in the modern history of land tenure and governance, if we in the development community can get our act together and use a newfound consensus on prioritizing the resolution of land issues to address the biggest development challenges of our time.

It is a critical period to move land tenure out as a constraint on equitable, efficient and ecologically sound resource use, in order to move development in with inclusive and sustainable agricultural systems, sustainable management of ecosystems and inclusive, green cities.

The stakes are high. Unprecedented levels of population growth, urbanization, land degradation, deforestation, water scarcity, and climate change are putting pressure on land-based resources in ways never before faced by humanity. These pressures threaten the resource base for society and call upon it to reach a new level of global success in managing its natural resources.

A New Consensus

Over the last five years, a new consensus has taken hold in the land professions that faster, more agile, “fit-for-purpose” approaches to recognizing land rights are needed, and that it is possible to achieve them technically and socially. In Africa for example, more progress has been made in the last five years than many imagined ever possible. There are some striking examples of what can be done when political commitment and best practice approaches to reforms are put in motion.

For someone who has spent their professional life working in the development trenches of the land sector, some of the shifts in the current moment are almost shockingly positive. A set of powerful ideas about improved approaches to governing land resources have arrived into mainstream development (many after long and difficult periods of gestation and experimentation). Suddenly we are hearing calls from around the globe for land systems that are fit-for-purpose, accessible, participatory, technologically-empowered, accountable, cost-effective, demand-driven, incentivized, community-led, place-based, contributing directly to sustainable livelihoods and communities. A set of approaches and tools which were still marginalized a decade ago are now recognized as critical mechanisms for ushering in sustainable development. The political and social context for land resource issues has become a global focus of political and media attention as both the grass-roots and consumer constituencies have become more effectively mobilized and aligned. Technology has become accessible in every corner of the planet.

New Paradigms for Land Resource Management

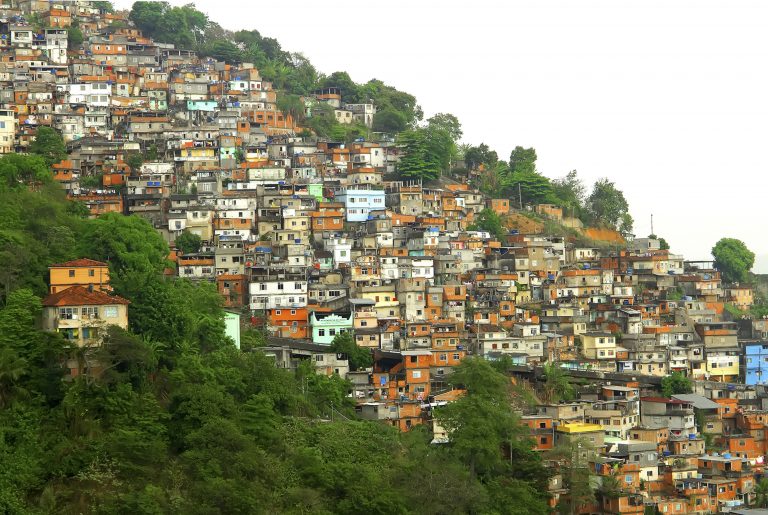

The demand for these new approaches and tools from across the globe and the political spectrum is strong and clear. Calls come from all groups and sectors, for secure and sovereign rural livelihoods, for responsible agricultural investment, from corporations to ensure land governance along the their entire supply chain (many will be watching Nestle!) for agroecology, for community-management of forests for better timber management and carbon storage, for indigenous self-determination, for the inclusion of informal settlements into the central life of cities, for the appreciation and value of place in making cities the engines of green growth for the future. The development challenges call for new paradigms of land resource management and tenure which take into account whole ecosystems and generate public goods.

Global and regional initiatives like UN-Habitat’s Global Land Tools Network, and the African Land Policy Initiative have become robust actors with strong operational models, resources and buy-in from governments. The concepts of good governance have been explicitly built into land policy making and its assessment and monitoring. Decentralization has made local governments the heart of much actual land governance. Grass-roots efforts for local solutions are multiplying, from Kenya’s Kibera to Brazil’s favelas. Many governments (e.g., Brazil, Indonesia, Tanzania) are making national attempts at pragmatic solutions to land governance which balance social and environmental goals with growth and investment aims. New streams of finance from urban value capture, agribusiness investment, ecosystem services and forest carbon payments create new opportunities for negotiating solutions about land tenure and use and achieving triple wins for livelihoods, productivity and sustainability.

Innovative Initiatives

New support organizations and networks have emerged in the last decade to help put the changes into action: Land Alliance is a “think and do tank” which seeks to amplify these changes to a new normal at a global scale. The Map My Rights initiative is harnessing the power of the crowd and the cloud to make land rights reform accessible and open, Namati (the name means “bend the curve”) is making legal services available in poor communities across through para-legals. These add to the pioneering contributions of UN-Habitat’s Global Land Tools Network like the social tenure domain model, Slum Dwellers’ International work in recognizing occupancy, the Rights and Resources Initiative development of community-forest tenure, and the advocacy of the members of the International Land Coalition. There are many, many more to mention. The donor community’s approaches have begun to evolve in the same directions, as suggested by the World Bank’s call for a new investment program for Africa.

The Challenge

Now the bad news. This change is still in its infancy and the scope of actual impact on the ground is relatively small. Three billion people, predominantly rural, live on less than $2.50 a day. A billion people live in informal settlements. Seventy-five percent of farmers do not have secure tenure on their land, including almost all African women. Thirteen billion hectares of forest are lost each year. Five million hectares of agricultural land is irreversibly degraded each year. The challenge is to make the change in global land governance happen more rapidly and widely, before the negative effects of these challenges become too big and locked in to handle.

The period 2015-2020 can bend the curve on land–based development challenges if political leaders, business and civil society join forces to face them at a new scale and pace.